A British team has modified the genome of 58 human embryos [1] using CRISPR-Cas9[2]. They said that they carried out their experiments to “study early human development” (see British scientists authorised to genetically handle human embryos). They specifically removed a gene from zygotes at the single-cell stage to “test the ability of the technique to decipher the functions of key genes“: “One way of establishing what a gene does in the developing embryo is to see what happens when it does not function” explained Kathy Niakan, who directed the research at the Francis Crick Institute. She hopes that other teams will investigate other key genes in future. The long-term aim of such studies is to “improve IVF treatments” and understand what causes miscarriage.

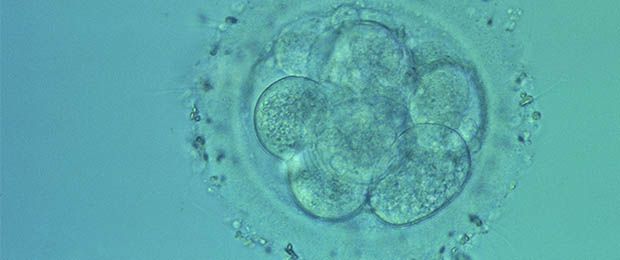

In the British study, the target gene was responsible for OCT4 protein production, which is usually activated during the first few days of embryo development. Scientists have studied murine embryos, human embryo stem cells and, more recently, human embryos. After seven days, the embryos were destroyed and “analysed“. At this point, the embryo comprises approximately 200 cells, which make up the “blastocyte“. The results published in the Nature journal show that the embryo needs OCT4 protein to form blastocytes.

Note from Gènéthique: During the summer, an American team published studies on the genetic modification of human embryos (see Genetically modified embryos: details of the American study are published). Their results were challenged after the summer break (see Genetically modified human embryos: results challenged).

[1] “Surplus” embryos created for in-vitro fertilisation.

[2] CRISPR-cas 9 – from a simple bacterial system to complex ethical issues

Nature, Heidi Ledford (20/09/2017); Reuters, Kate Kelland (20/09/2017)