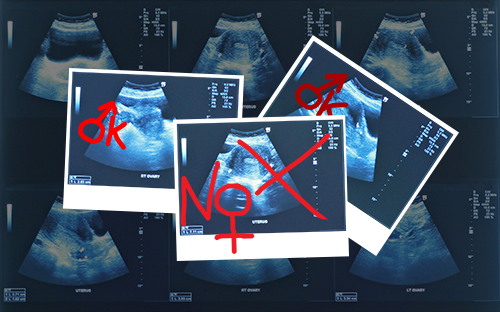

Although selective abortion is prohibited in China and India, in practice it is difficult to control and is frequently carried out. “If families can only have one child, they would prefer it to be a boy, who is more likely to work and financially support his parents”: in China, the one-child policy, which ran from 1975 to 2015, has considerably “disrupted” the gender ratio. Some Chinese regions peak at 120 men per 100 women, when the natural ratio is invariably around 105 boys to 100 girls[1]. The same problem exists in India, especially in rural areas, “where the birth of a girl is synonymous with economic burden and a dowry to pay”.

These customs of “son preference” were raised by Heather Barr, a women’s rights researcher, in an essay published in the wake of the 2019 Human Rights Watch report. She calculated that these unbalanced ratios have caused a shortfall of 80 million women in these two countries alone, China and India, the two most densely populated countries in the world.

One of the consequences of this imbalance is the difficulty that men have in finding a wife to guarantee descendants. The result is a real trafficking of women, especially by Chinese agencies that “import” Burmese women. Agencies promise them the earth to attract them to China. They are “finally purchased for $3,000 to $13,000 (depending on age and appearance) by families looking for a wife for their son”.

China and India “must act urgently to mitigate the effects of the decline in the number of women, and carefully consider the consequences of this shortage, including the links to trafficking and violence against women” concludes Heather Barr.

See also:

In India, doctor fights against female foeticide by offering to deliver baby girls free of charge

Selective abortions in Armenia: female population under threat

Selective abortion in Eastern Europe

Selective abortion, a reality in Canada

1] Average measured in 2012 by the World Health Organization (WHO).

Libération, Julia Toussaint (19/01/2019)